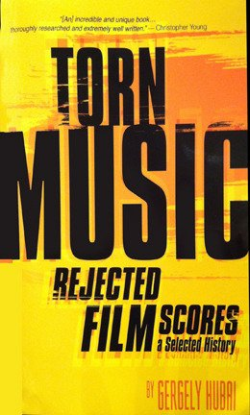

bookTorn Music: Rejected Film Scores - A Selected History

Book author: Gergely Hubai

Score rejection isn’t anything new. From the days of classical music, long before the invention of even the most rudimentary of early sound recording devices, to the early days before “Talkies”, scores have been dumped. It would only stand to reason when films came in to prevalence, creative heads would soon butt.

Soon, once films became as common place as the automobiles, people would make names for themselves within the industry, as in professions of times passed, be it a painter or an architect.

Once scores were recorded for film, rather than be played live at each presentation, a musical trail of forgotten history was left behind, only to be remembered in long forgotten interviews and biographical books after the fact, in brief summations.

Prominent composers were being dumped and scores tossed, instances were growing more remarkable as the films were. Then Kubrick created the first real public controversy by not only rejecting two very prominent composer’s scores, but not even telling one (North) until the composer found out by watching the screening.

Now not a year goes by without a minimum of recorded/partially recorded/demoed/or switches of composers before recording, of scores, where we don’t see over 40.

Until now, there has never been a full-fledged book on rejected scores. Bernstein’s Film Music Journal’s, Soundtrack! Magazine, and some film score books had addressed the subject at various light levels.

Early on the internet, a couple one-page websites kept small lists with no details, many titles unsolved. Then Film Score Monthly put together a listing, based on the information of the time, of about 40 or so titles.

And in early 2004, I, Justin Boggan, started a website. At the time meant to be more informational and kept updated, now expanded to the role of a historian, preserving information that would otherwise be lost to time, and speaking with people of every aspect of the process.

In late April, 2012, the book Torn Music was released. Chronicling about 500 stories of rejections and changes in composers from 1932 to 2008 (some chapters contain other stories not in the Table of Contents).

The author Gergely Hubai, is a score lover with a passion. He runs a film music blog, teaches music studies, writes linear notes for the occasional limited edition score releases, and obsesses about James Bond scores and their songs.

For Torn Music, Hubai didn’t simply copy and paste what we already know, for the most part, into a more critical stuffy formal fashion, but rather an expanded essay style on each film addressed. With a more professional and studied eye, the author delves into various production aspects, often precursors to forming trouble on the composer’s end – addressing the original approach of the first composer, as well occasioning to describe the sound of the tossed work.

The book sheds light on the process of re-scoring a foreign film both when shown in the U.S., and of American films re-scored overseas. Telling the tale of complexities that lead to such redoes, and addressing important examples.

It doesn’t just address films, but also covers some rejection of television series scores and even one video game.

Hubai’s book is littered with examples of musical history; how it changed and how Hollywood followed; how composers were once so important that director’s weren’t satisfied until they got a big “name” composer; and how studio practices of using music changed over time.

Without being heavy-handed, over doing it, or boring the reader with pointless details, Torn Music covers production troubles, casting and film changes, the hiring of the original composer, and often the fate of the film.

Some films are cursed from the beginning, and some composer’s fates are sealed early on. A fascinating read of troubles when making even the simplest B-movie.

Almost every chapter details the approach and sound of the rejected score and compares the replacement in such aspects as well.

The reader is left with such confounding rejection reasons, after the composer has recorded some or all their score, as:

- Simply not knowing whom the composer is and wanting somebody they know.

- Rejecting a score not because it was disliked, but to buy time for incomplete special effects, lying about the score to cover their butts.

- Believing the film was going to be big and garner awards and attention, and that a bigger name composer was needed.

- To even having to switch composer’s because one label had a right to release their music and they did not.

The reasons for rejection are varied and sometimes convoluted, thus no blanket policy can be thrown over the subject (though watch out if Barbara Streisand is in charge, or you’re the first composer on a Michael Mann film), but as the book shows, a troubled production is often a warning sign and thus a composer should learn the mistakes of history and be cautious.

Rejection of a score is almost never a reflection of the talent of a composer or the quality of their score. One has to really screw up on a production, as in one case in the book, before the ability of a composer gets him or her fired.

Even in stories such as “2001: A Space Odyssey” and “Torn Curtain” where you think you’ve heard it all before, new details are found; obscure information, rare quotes, letters, forgotten interview excerpts, and so on.

Torn Music is an exceedingly interesting read that every fan of film scores would enjoy. It’s a warning manual for all current and new composers, except John Williams, and what can and will eventually happen, even with previous collaborators.

There’s a reason David Raksin said, “You’re not a full-fledged screen composer until you’ve had a score thrown out of a picture.” And that one famous recording stage has a sign warning about rejection. Torn Music also serves as an assurance to composers on the common place practice of composer changes and hurdles one may have to clear in the process. No film and television composer’s library is complete without it, and video game composer’s should start paying attention, too as the practice is occurring more often in that field.

It’s replete with a forward by Christopher Young, and is around 400 pages when counting the chapters only. Though not being a “Once Upon a Time…” and “The End” novel, the reader can take in as much of the book as they want and put it down. They are not bound by anything but an evolution of films and scoring history.

This book was not rejected by Silman James Press.

Reviewed by Justin Boggan